Call us on +44 (0)20 7734 5985

Mostly dating from the end of the Georgian period up to the early 20th century, these serve to illustrate the intricacy and superlative craftsmanship which earned Henry Poole the reputation that put Savile Row on the map.

In 1869 the Lord Chamberlain’s office issued new guidelines governing the wearing of court dress. In an effort to standardise the appearance of gentlemen attending at court, the guidelines prescribed a suit of clothes cut from black silk velvet and trimmed with cut steel buttons. Hitherto court uniform had consisted of a coat and breeches of superfine cloth worn with a floral waistcoat. This in turn had descended from the lavishly decorated court clothes that were worn during the reign of King George III.

This new, more restrained style of dress became the regulation uniform for high sheriffs and retained some of the elements of dress from a previous age. Amongst these was a species of folding cocked hat known as a chapeau–bras which first made its appearance in the dying years of the 18th century, together with the black silk rosette worn at the back of the neck – the last vestige of the bag wig of the 1740s. The coat itself echoed the style of the 1780s though the advancement of 19th century tailoring techniques lent a more fitted silhouette to this later garment. To offset this more sober uniform, a great variety of cut steel buttons, shoe buckles and sword hilts were produced, allowing the wearer to express his personal taste.

Today we make shrieval court dress to much the same standards set a century or more ago. Whether for ladies or gentlemen, each suit is fully bespoke, cut and handmade from the finest Italian velvet, trimmed with a choice of buttons and shoe buckles in the correct court patterns. For ladies we offer a design service and are happy to advise on style and choice of material. We also undertake the alterations and renovation of court uniform.

First appearing in the reign of King George IV, the uniforms of ministers and members of the Privy Council were among the most expensive and time consuming to produce. Such uniforms were much admired and copied around the world, invariably utilising the national flora of the countries to which the wearers belonged.

An example of the ceremonial uniform worn by the Prime Minister and other government appointees of the Empire of Japan. The design incorporates the stylised form of the Paulownia Imperialis or “Empress tree”, the heraldic insignia or “mon” of the Mikado and is a good example of how foreign powers emulated the dress of the British Empire at its zenith.

Originally based on the uniform of General Officers, the uniforms of HM Lieutenants of reflected the military background of many of the appointees to that Office. The uniform gradually evolved throughout the nineteenth century; its development echoed that of military fashion and was guided by Henry Poole & Co, who twice drew up the regulations. In one form or other the uniform would be worn until the early nineteen fifties, when Lieutenants of Counties finally swapped their scarlet tunics for the blue service dress currently worn.

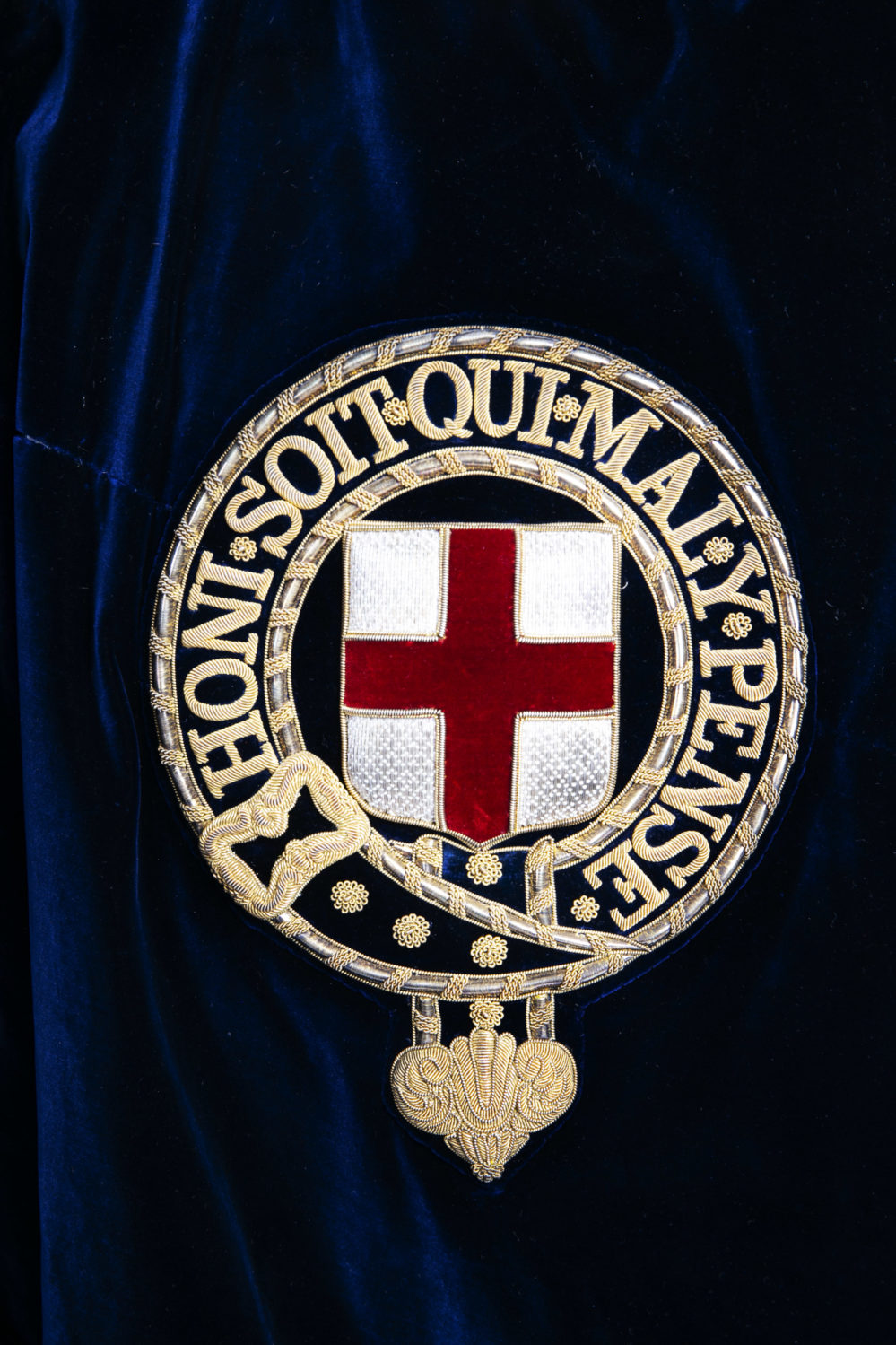

Made in 1906 for Charles Robert Wynn-Carington, 1st Marquess of Lincolnshire, the robes of the Order of the Garter have changed little since the Restoration. The badge of the Order embroidered on the left forepart of the robe bears the motto HONI SOIT QUI MAL Y PENSE or “Shame unto he who thinks evil of it” in plain English.

Among the several examples of servants dress livery held within the Henry Poole archive, this example is perhaps the most lavish, having over sixty yards of heavy silver gilt lace sewn onto it. In the era before the motor car, such elaborate livery uniforms were a common sight and a lucrative source of income for the elite houses of Savile Row including Henry Poole, whose livery trade was so extensive that for over thirty years it was housed in separate premises until after the First World War, when it was reabsorbed into the main premises of the company.